Poverty in America and What the Church Can Do – by Leslie Woods

Frequently, and especially in the summer months, the PC(USA)’s Office of Public Witness in Washington, DC, has the opportunity to welcome groups of Presbyterians from all over the country. Many of these groups have come to the nation’s capital to engage in urban immersion mission and service trips, whose focus is learning about and alleviating poverty. Washington, DC has the third highest poverty rate in the country, after Mississippi and Louisiana. When these groups come to visit the Office of Public Witness, they frequently ask me or one of my colleagues to speak about public policy issues that relate to their hands-on experience of grim poverty, homelessness, and hunger.

Frequently, and especially in the summer months, the PC(USA)’s Office of Public Witness in Washington, DC, has the opportunity to welcome groups of Presbyterians from all over the country. Many of these groups have come to the nation’s capital to engage in urban immersion mission and service trips, whose focus is learning about and alleviating poverty. Washington, DC has the third highest poverty rate in the country, after Mississippi and Louisiana. When these groups come to visit the Office of Public Witness, they frequently ask me or one of my colleagues to speak about public policy issues that relate to their hands-on experience of grim poverty, homelessness, and hunger.

Where to begin?

Because most of these groups are either youth groups or intergenerational, where youth and children are present, I like to start with a story. How many of you have heard the story of the people in the river? No?

The river and helping those trapped there

Well, one day, we are all gathered on a riverbank, enjoying our church picnic together. Suddenly, one of you notices a person out in the river. He’s crying out for help. You alert the rest of us and we all rush in the save him. We drag him out of the river, but before we can ask him what happened, we see another person trapped in the current on her way by, screaming and crying out in fear. We pull her to safety too, but the people just keep coming. It’s exhausting work, but what else can we do, but stay in that river pulling out one person at a time? Finally, a small group gets together and says to the rest of us: “you all stay here and keep helping those who are trapped in the river. Meanwhile, we’ll go upstream and find out what’s pushing the people into the river in the first place. Maybe there’s something we can do to stop it, and then there won’t be so many who reach out to us for help.”

That’s my way of explaining what we are trying to do in the Office of Public Witness. Every day we ask questions about why and who is throwing the people into the river.

So, let’s ask it — what is throwing the people into the river of crushing poverty and what can we, as individuals and as the body of Christ, do to prevent it?

Poverty is a vicious cycle that trapped more than 46 million U.S. men, women, and children in 2010 (according to the most recent Census Bureau Report). It is a cycle that I believe begins with poor wages and could end with repairing the wage inequities in our system. And by wage inequities, I refer to two major flaws – income inequality and the wage gender gap.

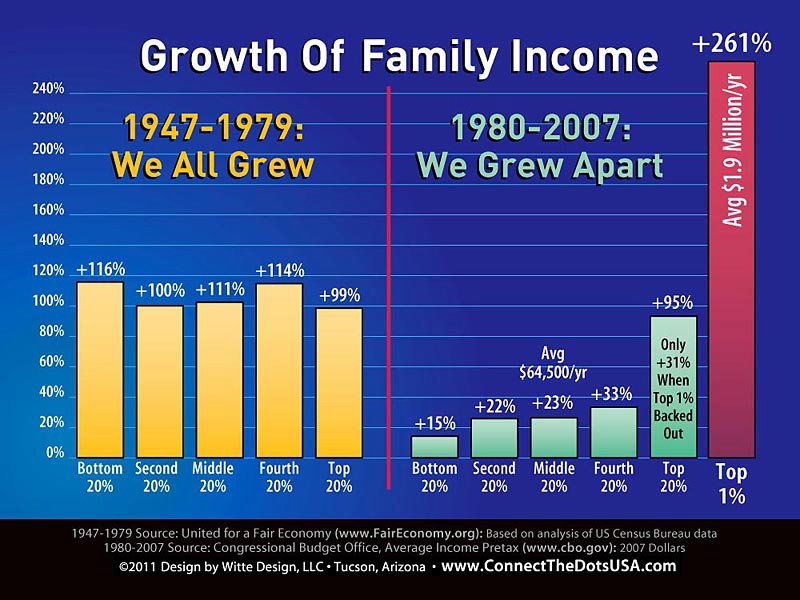

Income inequality refers to the gap between the top and the bottom of the income scale. According to a United for a Fair Economy analysis of Census and Congressional data, income growth from 1947-1979 was about the same at all levels of the income scale. That means that the poorest 20 percent of families enjoyed income growth / wage gains at about the same rate as the wealthiest 20 percent. But from 1980 to the present, the rate of wage growth for the bottom 99 percent has slowed and the bottom 20 percent has suffered only minimal gains compared to the rest of the economy. In contrast, the top 1 percent of the income scale has enjoyed such a dramatic rate of increase at the expense of its fellows that it is staggering to behold (see graph). Indeed, nearly half of the nation’s wealth is owned by the top one percent of the income scale.

The other serious injustice in our compensation system is the wage gender gap. Statistics show that, on average, women earn about 80 cents for every dollar earned by their male colleagues. When the Equal Pay Act was first enacted in 1963, a woman who worked full-time earned, on average, 59 cents for every dollar earned by a man. Clearly, over the decades, this gap has narrowed, but it has not disappeared. And it has lasting consequences for women and the families they support. According to The Wage Project, over a lifetime (47 years of full-time work), a female high school graduate will earn an average of $700,000 less than a male colleague. A female college graduate suffers a loss of $1.2 million over her work life and a female professional school graduate will earn $2 million less in her lifetime than her male counterparts.

The situation holds true for Presbyterian clergy women too, who, according to a cursory study in God’s Work in Women’s Hands: Pay Equity and Just Compensation, approved by the 218th General Assembly (2008), earn on average 27 percent less than male clergy, are less likely to be the lead pastor of their congregation, and have fewer opportunities to serve large congregations.

But despite the pressing need to address pay equity among our own clergy, the gender wage gap predictably affects those at the bottom of the income scale most keenly. Women are disproportionately underpaid and overrepresented in what are known as pink-collar jobs: retail, child care, and domestic work, where not only is the pay low, but benefits are rare.

So, what are we to do? How do we keep the people from getting tossed into the river and trapped there in the current of cyclical and inescapable poverty?

How to respond

First, we must support the creation of good jobs – not just jobs, but good jobs that pay decent wages and provide the sort of benefits that people need to survive, like health care and paid sick leave. Second, we need to support legislative efforts and work supports to make the wage and compensation system more just. Such policies include higher minimum wage, living wage ordinances, paid sick leave, child care support and accessible transportation. Third, efforts to put more power in the hands of workers, either to report and receive compensation over wage discrimination after the fact, or to negotiate contracts with better wages and working conditions are essential for improving the current situation.

We must also address the rampant individualism that seems to have taken over our culture in the last couple of decades. A world where the rich get richer while the middle class falls into poverty and the poor get even poorer requires a reevaluation of our priorities. Why have we allowed such a tiny segment of our neighbors to amass such tremendous wealth at the expense of the rest? Why have we allowed the sort of deregulation that permits big corporations and banks to make decisions based only on investors’ interest without any reference to the common good? Why has our collective commitment to supporting each other and our communities through our tax dollars become anathema?

And in the meantime, we have to keep pulling the people out of the river, not only through our local ministries of charity and mercy, but also at the government level, where our commitment to each other finds collective and communal expression in how we choose to spend our national resources (i.e. our tax dollars). As the sluggish recovery fails to reach the majority of working Americans, and the specter of a double-dip recession looms above us like a storm cloud, we must support interim measures that will both pull people out of the river and keep them from falling in. We need government programs that create jobs, provide unemployment benefits for laid-off workers, increase programs like Food Stamps, which are keeping people from falling further into poverty, and other measures at all levels of government that work to create a safety net and protect those who are living in or near poverty.

Asking the wrong questions

As I reflect on the conversations that are taking place at the national level, it strikes me that we’re asking the wrong questions. Yes, the nation has a long-term deficit problem, but how to reduce the deficit in the short-term is not the right question – and of course, that’s where our national decision-makers are focusing. The deficit is a long-term problem and deserves long-term solutions. Reducing the deficit this year will not only do little to improve our economic outlook, but will likely damage it. Many economists have pointed out that the best stimulus to an ailing economy is job creation. The last several employment reports from the U.S. Department of Labor have shown only modest net job growth, in part because the public sector keeps cutting jobs. We need policies that will put people back to work, not force more lay-offs of teachers, firefighters, police officers, and other government workers.

Our role – keeping our brothers and sisters out of the river

So, I would argue that the role of the Church is to call our nation back to our collective commitment to each other – to be our brothers’ and sisters’ keepers and to ensure that everyone has enough to make ends meet. We need to call our decision-makers back to the reality of devastating poverty in this nation, and our need for a public partnership to address it. Those who claim that it is the role of the church alone to minister to those living in poverty fail to recognize the fundamental truth that our ministries alone cannot address the massive and growing need. We require partnership with all of the kinds of policies mentioned above, and more, in order to meet increasing and overwhelming need. Ministries of charity and mercy are essential, and we will continue to pull people out of the river with every resource we can muster, but the broader community, including government, must do its share by keeping people out of the river and pulling the unfortunate back out.