Disasters, The Poor, The Rich, and the Church – by José Irizarry

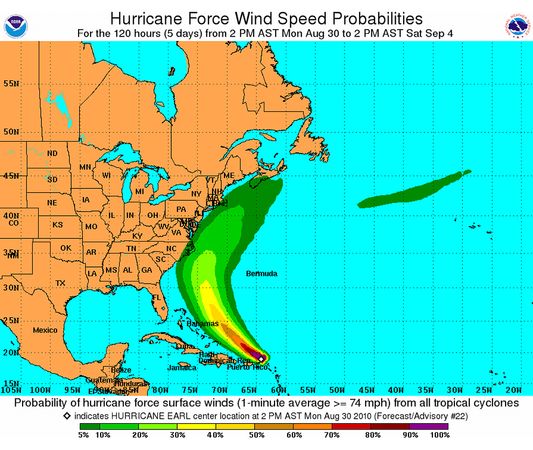

On August 29, 2010, as the American collective memory was reawakened to the social, political, and affective impact of Hurricane Katrina’s devastation of the US gulf coast after five years of its occurrence, a group of Caribbean islands scattered miles away were too concerned with preparations to confront the impending arrival of Hurricane Earl to pay much attention. In the island of Puerto Rico, that preparation started three days before the expected landfall. Within hours, stores were depleted of non-perishable food, first need articles, batteries, propane gas containers and electrical generators. Windows and doors were covered with plaid wood and metal sheets to protect homes and families from loose objects that act as projectiles when winds exceed 90 miles per hour. Since early hours, long lines of cars were formed at gas stations, filling-up tanks in case a local area was struck by high winds and floods and there was a need to pick up precious possessions and escape (even when “to escape” is only an euphemism on a 100×35 miles island surrounded by water). For a region prone to welcoming the impending immigration of storms from the African coast, every action and reaction to the possibility of being affected by a hurricane is calculated and carefully rehearsed.

While interpreters of the Katrina event placed responsibility (rightly so) on government agencies for the lack of preventive plans and a mismanaged response, in the case of the Caribbean island, preparations and preventive measures for these phenomena will initiate with little or no information provided by government agencies. Government agencies and politicians will enter into the media scene to share the usual dose of hysteria-conducive-histrionics which is more about political self-promotion than about offering important information for emergency readiness. By the same token, citizens are encouraged to supply themselves of many goods which promotes excessive consumerism. The potential crisis moves the economy in ways that makes the natural threat even desirable. In the case of Puerto Rico, the preventive stage of a natural disaster becomes political; whereas, in the United States, it is dealing with the aftermath that becomes political, as demonstrated by subsequent media obsession with katrinagate and, currently, with the inability of the US government to fulfill its financial commitment to support reconstruction in post-earthquake Haiti.

Disasters become news as they challenge our ideas of security in richer nations, and become marginal events when they stress the precarious position of poorer nations.

Along with the political dimension, the economic factor impinges significantly in addressing and interpreting the effects of natural disasters on the social order. It is commonly accepted that natural disasters tend to cause larger damage within impoverished communities that lack the basic infrastructure and the material resources to withstand their impact. In fact, in order to categorize a natural phenomenon as a “disaster,” its effect has to be appraised against the “normal” life-style and social condition of those affected. Crisis ensues when taken-for-granted services such as electricity, potable water and transportation become disrupted for those who are used to enjoying these privileges. However, those who lack these services in their day-to-day existence will show a certain degree of resilience towards the outcome of natural disasters unless life itself is threatened. Understood in this way, there is no separation between the social and the natural in experiencing and making-meaning out of natural disasters. The disaster becomes news as it challenges our ideas of political and economic security (as in the case of Katrina affecting US cities) and becomes a marginal event when it solely stresses the political and economic precariousness of poorer nations (as was the case with the recent floods in Pakistan and Vietnam and the fatal mudslides in México). While we may think that there is a universal tendency to demonstrate transnational empathy after a natural disaster, the truth is that our experience and interpretation of these socially-disrupting natural phenomena is highly contextual.

Haiti’s 2008 earthquake may seem like a counterargument to the idea of the poor nations’ invisibility in the midst of natural disasters, for this catastrophe received extensive media coverage and encouraged an expedient process international cooperation. Besides politics and economy, two other aspects provided the conceptual framework for experiencing and interpreting this event; race and theology. Since the Katrina crisis introduced the discourse of race into judging the social implications of natural disasters, countries became more susceptible to the sort of criticism and scrutiny they will be subjected to if response to the Haitian crisis was not adequate.

In turn, it will be insensitive for liberal democracies to demonstrate affinity to a distorted (and outdated) theological argument that seek effortless connections between the suffering of a nation and divine judgment. The provocative title on Lisa Miller’s Newsweek article “Why God Hates Haiti,” became a real inquiry for many who considered Haiti’s popular religions to be contrary to (the Christian) God’s will and a major reason for their predicament. I suspect that many churches combined their collection efforts to assist Haiti with deliberate preaching to either support or condemn this theological view. When confronted with human suffering, churches have often take hold of the theodicy argument to either justify the causes of natural disasters as divine responses to human behavior or to encourage un-reflexive resignation to the inscrutability of God’s will, who, in the best of cases, accompanies the human being in its suffering. It is pertinent to note that in responding to one of the most corporeal and concrete experiences of humanity; suffering, the church is prompt to offer as a balm one of its more abstract and speculative theological arguments; theodicy. In the midst of human suffering, the theological concreteness of such themes as redemption, historical salvation, covenantal grace, and divine solidarity may become the language of the church.

The church, called by God to announce good news of salvation to all people, cannot afford to remain concerned with mere theological queries when addressing human suffering provoked by natural disasters (despite the fact that there is a great spiritual need after a society experiences a crisis). The Church may need to address the political, economic, cultural and theological issues that factor into interpreting and responding to a natural disaster which is, after all, a social problem not a problem of nature (which is only acting on behalf of its own regeneration).

The church has a role as social communicator.

The first thing that the church should acknowledge is its role as social communicator. The church, as part of a larger ecology of communication and education, is in a privileged position for convening and instructing people in moments of crisis. Every disaster generates a great need for information and churches can become, in preventive stages, a gathering place for sharing information, especially when other energy-dependent media can fail. The communicative role should center in the sharing of essential information about how to prepare and how to seek assistance in case of emergency. In tandem, the church should provide a word of realistic hope as well as a more humane interpretation of God’s relation to suffering.

The spirit of solidarity should permeate the Church’s response to those adversely affected by the disaster and should move us to provide material and financial support when possible. However, that spirit of solidarity may need to be contained by an ordered plan that will channel those contributions through organizations authorized to offer first response to disaster emergencies. Many times our urgency to help may precipitate our intromission into affected areas in ways that can create more chaos if efforts are not coordinated. In Haiti, for example, the assistance of some churches working independently created social unrest when these churches were unable to supply sufficiently all members of particular communities. The church should understand also that the need for material assistance will be reduced during times of crisis caused by natural disasters if there is a continuous flow of mission money to impoverished countries assisting them to build stronger infrastructure, thus reducing vulnerability. Christian charity should not be reactive, it should become the way we continuously express our faith to a God who has called us to encounter him in the face of the other.

The need for material assistance during a crisis can be reduced by the continuous flow of moneys to assist in building infrastructure and reduce vulnerability.

The Church affirms the need for God in the fragmentation of the word and the frailty of creation. This affirmation may help to counter the dominant political view that natural disasters are just exceptions to an otherwise “normal” life. The practical implication of this theological critique is that emergency management, risk analysis, and disaster mitigation should be part of social planning at every moment, is the way we care for both the human person and creation. In lieu of that caring role, the church should also create networks of support to provide the care and counseling needed when families and communities are overtaken by the sense of loss that follows a natural disaster. The Church also promotes the care of creation when it conveys that our exploitative behavior towards nature places human communities at risk and that social and economic development should be done in harmony with nature, a nature that represents the first gift of God to a humanity in need of a stage for its salvation.

Pingback: Tweets that mention Disasters, The Poor, The Rich, and the Church – by José Irizarry | Ecclesio.com -- Topsy.com

Jose, you have given us much to reflect upon. Thanks for removing this discussion from a US center. I particularly affirm your sense of the need for continuous flows of money to avoid the need for enormous aid when disaster strikes. However, as a member of a “mainline” denomination that is in significant decline, I really wonder how to accomplish this. Having served in mission overseas, I know that many Christians on the left see missions work as not a priority — yet the kind of development work to which you refer is part of our calling as disciples and as members of the one Body. What are your thoughts on how to address this conundrum?

Cynthia, your observation about church decline and the lack of focus on international missions within our “mainline” denominations presents a real challenge to accomplishing the church’s role in relation to poor countries affected by natural disasters, but not an insurmountable one. The fact that the church has forgotten the global dimension of the “Great Commission” and has made congregational sustainability the locus of any proclamation on stewardship, supports my conviction that this work requires some critical repositioning of our theological priorities (which can follow up with a more conscious prioritization of their mission and their budget lines). The first challenge then is not quantitative, it points to the quality of life that the church wants to embrace even in the midst of scarcity. When natural disasters occur, institutions and organizations respond with the measure required by their own missions, objectives and ethos; the reason why many poor countries, as well as small organizations and communities, were able to promote among its members a sense of solidarity towards those affected by natural disasters moving large amounts of material and financial resources into damaged areas. It certainly required, from these small and poor communities, some type of sacrifice as they balanced their internal needs vis a vis the immediacy of their suffering neighbors It is precisely in this time of decline that the church may want to consider if providing safety and well-being to another human being is worth loosing a couple of congregational and denominational programs.

The previous response was posted by me with no intention to be anonymous.

Thanks, Jose; I had thought it might be you! Your response gets to the heart of what we believe about the church and the mission and nature of the ecclesia — an issue we discuss each week here.

It also has to do with stewardship and how we raise and spend the money that God bestows upon us. As mainline denominations decline it is seemingly difficult to interpret what the church is and what our role is in the world. (I say seemingly because I am pretty sure we aren’t doing a very good job.) Two quick thoughts on this:

The Advocacy Committee for Racial Ethnic Concerns, a committee of the General Assembly PCUSA, put forward a resolution to the 2010 GA to form a study committee on the nature of the church. The impetus included some of the issues you raise in your post, Jose. This resolution was passed and the committee is to have its first meeting soon. I am praying that some new insight can be realized and articulated by this group; we are hoping for a diverse gathering.

The other thought is that Financial Stewardship in the Midst of Recession is the theme for next week’s ecclesio.com. This is a crucial issue for all of us in the church. I hope you will read and join the conversation started here next week. Carol Howard Merritt and Teresa Chavez Sauceda will join me.

Pingback: The Church and Disaster Relief | Ecclesio.com