Martin Luther King Jr. Day: Response to “Letter from the Birmingham Jail”

Read J. Kameron Carter’s Essay, “An Extreme Social Vision: On King’s ‘Letter from a Birmingham Jail'”

Read John Senior’s Essay, “Why We Wait, and How Not To”

As a EuroAmerican Christian, reading the letter of the white clergymen who wrote to King is embarrassing.

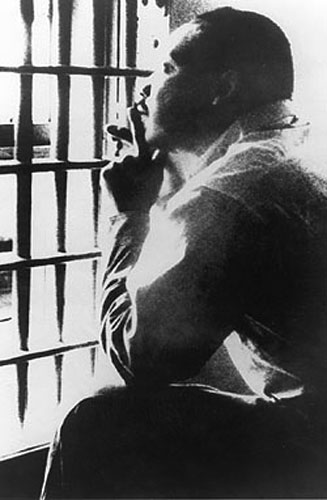

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s letter written from the jail at Birmingham has become known as a thoughtful and provocative early piece, unique in his body of published work. King wrote the letter in response to an editorial published in the local paper by white clergymen criticizing King and others who were protesting civil rights abuses in Birmingham, particularly those (like King) who were named “outsiders”. In this response, three aspects of the letter exchange are highlighted.

First, as a Euroamerican Christian, it is embarrassing to read the letter of the white clergymen (whose members included one Presbyterian, I am sad to say). The willingness of these men to critique people working under pressures of which they had no experience is a time-honored and standard practice of those blessed with hegemonic privilege. As such, it (like all such practices) displays a level of ignorance and lack of compassion that shocks and saddens. The fact that these men may have seen their actions and their letter as “progressive” in relationship to the “Negro” (sic) only deepens the problem. Trust in the authorities and the rule of law to solve a problem is not possible when those same authorities and laws have repeatedly exacerbated those same problems. Plainly, the rules are different for different people and they are applied differently or not applied at all depending on one’s station and status. But the clergymen ignored the history and asked for trust and calm. In particular, the commendation for law enforcement officials demonstrates a lack of awareness of the complexity, difficulty and danger inherent in the issues at hand.

King brought the “hidden transcript” of a subordinate, oppressed people into the open through his response.

Second, King’s response brought what James Scott would call a “hidden transcript” into the open and published it abroad. In Domination and the Arts of Resistance:Hidden Transcripts, Scott analyzes the knowledge base and skill-sets learned as a requisite path to survival by subordinate peoples. The capacity for bi- and tri-lingual fluency based on context common among those who are oppressed is unknown among the dominant, Scott suggests. This is because those who have the power to dominate a context require others to speak their language and do not generally choose to become fluent in the cultural nuance of different forms of speech. Further, dominant groups require forms of address from subordinate groups and individuals that indicate their lower station. Scott’s research shows that common shows of hegemonic privilege can actually be put to use by subordinate groups and individuals, who can (and often do) quietly resist the power of the dominant, by responding in ways that seem (on the surface) understandable and respectful but in fact indicate a deeper meaning or meanings, often the opposite of the words’ literal meaning.

Through publishing his analysis of the “hidden transcript” of what it meant to be African-American in the US during and before the civil rights era, King showed the holes in the argument posed by the white clergymen. Their letter encouraged using the “proper channels”, to find a “constructive and realistic approach” to racial problems, and to pursue issues through the courts. King pointed out that as African-Americans faced murder, violence and the denial of civil rights, all of which were being supported by the courts and those who worked in “the proper channels”, other strategies would have to be identified. His letter is a master class in “hidden transcript” translation, an exercise in explaining what would have seemed obvious to those who were oppressed, but to those who were dominant would be completely incomprehensible without this interpretation.

King’s letter continues to resonate because the issues are still with us.

Finally, King’s letter continues to resonate today because the issues he addressed are still with us. The 1963 letters laid out two experiences of living in the US, two views of history, and two views of the church. These pairs continue to exist.

This year, the 150th anniversary of the US Civil War will be remembered by many, and celebrated by some. Last month, South Carolina, the first state to secede, had a grand ball to remember, and the SC Sons of Confederate Veterans bought airtime to encourage reflection in the state on the blow struck for freedom by the 170 who signed the Ordinance of Seccession. Their website calls the Civil War the “Second American Revolution”, and lauds Confederate soldiers for fighting for the rights guaranteed to them by the Constitution. Slavery is noticeably absent in the advertising and website copy, although the “Declaration of Immediate Causes” for the state’s secession includes the words “slavery”, “slaves” and “slave” a cumulative total of 33 times. The issue of states’ rights, promoted by these organizations as more compelling and more causative to the coming of the War, leads the historical interpretation charge in this campaign to assist people to remember in politically-correct (albeit revisionist) manner.

In our current societal context, the relationship of race and power, never a simple matter, has become ever-more complex. The Tea Party movement, a many-headed initiative that emerged between the election and inauguration of the first US President of color, is feeling and flexing considerable political muscle; at this moment, states’ rights makes good copy and reliably attracts a following. Talking about slavery, on the other hand, is distasteful and offputting, and brings in messy reminders of a past from which many Euroamerican citizens would choose to distance themselves. Because these citizens are inevitably and invariably among the comparatively powerful in US society (that is, they are all white) – as their forebears were during the Civil War period, and when Dr. King and white clergy exchanged letters in 1963 – they can expect to have the narrative constructed and reported in ways coherent to them.

The racism – sometimes subtle, sometimes overt, always unapologetic – inherent in both the life of the Tea Party and many of the present initiatives planned to “celebrate” the US Civil War is perilous to the fabric of a healthy society and cannot be ignored. Particularly for we who follow Jesus, the use of language with religious and quasi-Christian overtones and undertones employed in the service of programs that work toward oppressive ends should alarm and move us to reflect and to act. During the Civil War President Lincoln identified the reality of conflicting sides founding their arguments on scripture and looking to the same God for forgiveness, comfort and support in his 2nd Inaugural Address. In Birmingham, those who criticized King identified themselves as clergy, implying that their statements were of God. The same routine continues in our time.

The power of Dr. King’s letter continues to resonate for us today, for he speaks into our context and challenges the sinful use of religious symbols and authority in order to prop up violence, oppression and prejudice. This sin was present during the Civil War and during the Civil Rights movement; of course it continues today.[1] Those who follow Jesus can helpfully reflect on Dr. King’s letter, so to advance in our own capacity to see and understand the hidden racial transcripts of our time and take the courage necessary to challenge them in the name of God.

WEDNESDAY: J. Kameron Carter, Duke Divinity School, and John Senior, Practical Matters, join the conversation.

Editor’s Note: Ecclesio.com launched in October 2010, and so this is our first observance of Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. This week, we offer three reflections in honor of Dr. King’s “Letter from the Birmingham Jail”, and invite others to share their reflections on this key work.

Read J. Kameron Carter’s Essay, “An Extreme Social Vision: On King’s ‘Letter from a Birmingham Jail'”

Read John Senior’s Essay, “Why We Wait, and How Not To”

[1] Even in commemorations of Dr. King and celebrations of his legacy, people can and do use Dr. King himself to prop up their arguments; last week, King’s memory was summoned to support US wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Thank you for Dr. Cynthia Holder Rich for a timely reflection on the “Letters from the Birmingham Jail”. As an African-American woman I am grateful for the courage and prophetic voice of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in the cause of freedom. Though much progress has been made (I can almost enter any public building without fear of being run out because my ‘kind’ is not welcome); I am troubled by the backlash aganist racial equity clothed in the rhetoric of ‘states rights’. The racial divide, in these tough economic times, seems to be getting wider. Many overt forms of racism are gone, but more subtle forms are on the rise. On this day, where many in our nation are honoring a man who worked for racial equity and freedom for all who were oppressed, may we all decide to take a stand for justice and racial equity.

Thanks Michelle for your comment; I am also troubled by the ways in which racism finds a way through to continue despite the obvious progress made. It calls for continued commitment to name it, stand against it, and offer constructive alternatives to blaming, demeaning or denying opportunity to anyone on the basis of color or creed.