The Play’s the Thing – Chris Hedges

I began teaching a class of 28 prisoners at a maximum-security prison in New Jersey during the first week of September. My last class meeting was Friday. The course revolved around plays by August Wilson, James Baldwin, John Herbert, Tarell Alvin McCraney, Miguel Piñero, Amiri Baraka and other playwrights who examine and give expression to the realities of America’s black underclass as well as the prison culture. We also read Michelle Alexander’s important book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. Each week the students were required to write dramatic scenes based on their experiences in and out of prison.

I began teaching a class of 28 prisoners at a maximum-security prison in New Jersey during the first week of September. My last class meeting was Friday. The course revolved around plays by August Wilson, James Baldwin, John Herbert, Tarell Alvin McCraney, Miguel Piñero, Amiri Baraka and other playwrights who examine and give expression to the realities of America’s black underclass as well as the prison culture. We also read Michelle Alexander’s important book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. Each week the students were required to write dramatic scenes based on their experiences in and out of prison.

My class, although I did not know this when I began teaching, had the most literate and accomplished writers in the prison. And when I read the first batch of scenes it was immediately apparent that among these students was exceptional talent.

The class members had a keen eye for detail, had lived through the moral and physical struggles of prison life and had the ability to capture the patois of the urban poor and the prison underclass. They were able to portray in dramatic scenes and dialogue the horror of being locked in cages for years. And although the play they collectively wrote is fundamentally about sacrifice—the sacrifice of mothers for children, brothers for brothers, prisoners for prisoners—the title they chose was “Caged.” They made it clear that the traps that hold them are as present in impoverished urban communities as in prison.

The mass incarceration of primarily poor people of color, people who seldom have access to adequate legal defense and who are often kept behind bars for years for nonviolent crimes or for crimes they did not commit, is one of the most shameful mass injustices committed in the United States. The 28 men in my class have cumulatively spent 515 years in prison. Some of their sentences are utterly disproportionate to the crimes of which they are accused. Most are not even close to finishing their sentences or coming before a parole board, which rarely grants first-time applicants their liberty. Many of them are in for life. One of my students was arrested at the age of 14 for a crime that strong evidence suggests he did not commit. He will not be eligible for parole until he is 70. He never had a chance in court and because he cannot afford a private attorney he has no chance now of challenging the grotesque sentence handed to him as a child.

My stacks of 28 scenes written by the students each week, the paper bearing the musty, sour smell of the prison, rose into an ungainly pile. I laboriously shaped and edited the material. It grew, line by line, scene by scene, into a powerful and deeply moving dramatic vehicle. The voices and reality of those at the very bottom rung of our society—some of the 2.2 million people in prisons and jails across the country, those we as a society are permitted to demonize and hate, just as African-Americans were once demonized and hated during slavery and Jim Crow—began to flash across the pages like lightning strikes. There was more brilliance, literacy, passion, wisdom and integrity in that classroom than in any other classroom I have taught in, and I have taught at some of the most elite universities in the country. The mass incarceration of men and women like my students impoverishes not just them, their families and their communities, but the rest of us as well.

“The most valuable blacks are those in prison,” August Wilson once said, “those who have the warrior spirit, who had a sense of being African. They got for their women and children what they needed when all other avenues were closed to them.” He added: “The greatest spirit of resistance among blacks [is] found among those in prison.”

I increased the class meetings by one night a week. I read the scenes to my wife, Eunice Wong, who is a professional actor, and friends such as the cartoonist Joe Sacco and the theologian James Cone. Something unique, almost magical, was happening in the prison classroom—a place I could reach only after passing through two metal doors and a metal detector, subjecting myself to a pat-down by a guard, an X-ray inspection of my canvas bag of books and papers, getting my hand stamped and then checked under an ultraviolet light, and then passing through another metal door into a barred circular enclosure. In every visit I was made to stand in the enclosure for several minutes before being permitted by the guards to pass through a barred gate and then walk up blue metal stairs, through a gantlet of blue-uniformed prison guards, to my classroom.

The class, through the creation of the play, became an intense place of reflection, debate and self-discovery. Offhand comments, such as the one made by a student who has spent 22 years behind bars, that “just because your family doesn’t visit you doesn’t mean they don’t love you,” reflected the pain, loneliness and abandonment embedded in the lives of my students. There were moments that left the class unable to speak.

A student with 19 years behind bars read his half of a phone dialogue between himself and his mother. He was the product of rape and tells his mother that he sacrificed himself to keep his half brother—the only son his mother loves—out of prison. He read this passage in the presentation of the play in the prison chapel last Thursday to visitors who included Cornel West and James Cone.

Terrance: You don’t understand[,] Ma.

Pause

Terrance: You’re right. Never mind.

Pause

Terrance: What you want me to say Ma?

Pause

Terrance: Ma, they were going to lock up Bruce. The chrome [the gun] was in the car. Everyone in the car would be charged with murder if no one copped to it …

Pause

Terrance: I didn’t kill anyone Ma… Oh yeah, I forgot, whenever someone says I did, I did it.

Pause

Terrance: I told ’em what they wanted to hear. That’s what niggas supposed to do in Newark. I told them what they wanted to hear to keep Bruce out of it. Did they tell you who got killed? Did they say it was my father?

Pause

Terrance: Then you should know I didn’t do it. If I ever went to jail for anything it would be killing him … and he ain’t dead yet. Rape done brought me into the world. Prison gonna take me out. An’ that’s the way it is Ma.

Pause

Terrance: Come on Ma, if Bruce went to jail you would’uv never forgiven me. Me, on the other hand, I wasn’t ever supposed to be here.

Pause

Terrance: I’m sorry Ma … I’m sorry. Don’t be cryin’. You got Bruce. You got him home. He’s your baby. Bye Ma. I call you later.

After our final reading of the play I discovered the student who wrote this passage sobbing in the bathroom, convulsed with grief.

In the play when a young prisoner contemplates killing another prisoner he is given advice on how to survive prolonged isolation in the management control unit (solitary confinement, known as MCU) by an older prisoner who has spent 30 years in prison under a sentence of double life. There are 80,000 U.S. prisoners held in solitary confinement, which human rights organizations such as Amnesty International define as a form of torture. In this scene the older man tells the young inmate what to expect from the COs, or correction officers.

Ojore (speaking slowly and softly): When they come and get you, ’cause they are gonna get you, have your hands out in front of you with your palms showing. You want them to see you have no weapons. Don’t make no sudden moves. Put your hands behind your head. Drop to your knees as soon as they begin barking out commands.

Omar: My knees?

Ojore: This ain’t a debate. I’m telling you how to survive the hell you ’bout to endure. When you get to the hole you ain’t gonna be allowed to have nothing but what they give you. If you really piss them off you get a ‘dry cell’ where the sink and the toilet are turned on and off from outside. You gonna be isolated. No contact. No communication.

Omar: Why?

Ojore: ’Cause they don’t want you sendin’ messages to nobody before dey question some of da brothers on the wing. IA [internal affairs officers] gonna come and see you. They gonna want a statement. If you don’t talk they gonna try and break you. They gonna open the windows and let the cold in. They gonna take ya sheets and blankets away. They gonna mess with ya food so you can’t eat it. An’ don’t eat no food that come in trays from the Vroom Building. Nuts in Vroom be spittin’, pissin’ and shittin’ in the trays. Now, the COs gonna wake you up every hour on the hour so you can’t sleep. They gonna put a bright-ass spotlight in front of ya cell and keep it on day and night. They gonna harass you wit’ all kinds of threats to get you to cooperate. They will send in the turtles in their shin guards, gloves, shank-proof vests, forearm guards and helmets with plexiglass shields on every shift to give you beat-downs.

Omar: How long this gonna go on?

Ojore: Til they break you. Or til they don’t. Three days. Three weeks. You don’t break, it go on like this for a long time. An’ if you don’t think you can take it, then don’t start puttin’ yerself through this hell. Just tell ’em what they wanna know from the door. You gonna be in MCU for the next two or three years. You’ll get indicted for murder. You lookin’ at a life bid. An’ remember MCU ain’t jus’ ’bout isolation. It’s ’bout keeping you off balance. The COs, dressed up in riot gear, wake you up at 1 a.m., force you to strip and make you grab all your things and move you to another cell just to harass you. They bring in dogs trained to go for your balls. You spend 24 hours alone one day in your cell and 22 the next. They put you in the MCU and wait for you to self-destruct. An’ it works. Men self-mutilate. Men get paranoid. Men have panic attacks. They start hearing voices. They talk crazy to themselves. I seen one prisoner swallow a pack of AA batteries. I seen a man shove a pencil up his dick. I seen men toss human shit around like it was a ball game. I seen men eat their own shit and rub it all over themselves like it was some kinda body lotion. Then, when you really get out of control, when you go really crazy, they got all their torture instruments ready—four- and five-point restraints, restraint hoods, restraint belts, restraint beds, stun grenades, stun guns, stun belts, spit hoods, tethers, and waist and leg chains. But the physical stuff ain’t the worst. The worst is the psychological, the humiliation, sleep deprivation, sensory disorientation, extreme light or dark, extreme cold or heat and the long weeks and months of solitary. If you don’t have a strong sense of purpose you don’t survive. They want to defeat you mentally. An’ I seen a lot of men defeated.

The various drafts of the play, made up of scenes and dialogue contributed by everyone in the class, brought to the surface the suppressed emotions and pain that the students bear with profound dignity. A prisoner who has been incarcerated for 22 years related a conversation with his wife during her final visit in 1997. Earlier his 6-year-old son had innocently revealed that the woman was seeing another man. “I am aware of what kind of time I got,” he tells his wife. “I told you when I got found guilty to move on with your life, because I knew what kind of time I was facing, but you chose to stick around. The reason I told you to move on with your life was because I didn’t want to be selfish. So look, man, do what the fuck you are going to do, just don’t keep my son from me. That’s all I ask.” He never saw his child again. When he handed me the account he said he was emotionally unable to read it out loud.

Those with life sentences wrote about dying in prison. The prisoners are painfully aware that some of them will end their lives in the medical wing without family, friends or even former cellmates. One prisoner, who wrote about how men in prolonged isolation adopt prison mice as pets, naming them, carefully bathing them, talking to them and keeping them on string leashes, worked in the prison infirmary. He said that as some prisoners were dying they would ask him to hold their hand. Often no one comes to collect the bodies. Often, family members and relatives are dead or long estranged. The corpses are taken by the guards and dumped in unmarked graves.

A discussion of Wilson’s play “Fences” became an exploration of damaged manhood and how patterns of abuse are passed down from father to son. “I spent my whole life trying not to be my father,” a prisoner who has been locked up for 23 years said. “And when I got to Trenton I was put in his old cell.”

The night we spoke about the brilliant play “Dutchman,” by LeRoi Jones, now known as Amira Baraka, the class grappled with whites’ deeply embedded stereotypes and latent fear of black men. I had also passed out copies of Robert Crumb’s savage cartoon strip “When the Niggers Take Over America!,” which portrays whites’ fear of black males—as well as the legitimate black rage that is rarely understood by white society.

The students wanted to be true to the violence and brutality of the streets and prison—places where one does not usually have the luxury of being nonviolent—yet affirm themselves as dignified and sensitive human beings. They did not want to paint everyone in the prison as innocents. But they know that transformation and redemption are real.

There are many Muslims in the prison. They have a cohesive community, sense of discipline and knowledge of their own history, which is the history of the long repression and subjugation of African-Americans. Most Muslims are very careful about their language in prison and do not curse, meaning I had to be careful when I assigned parts to the class.

There is a deep reverence in the prison for Malcolm X. When the class spoke of him one could almost feel Malcolm’s presence. Malcolm articulated, in a way Martin Luther King Jr. did not, the harsh reality of poor African-Americans trapped in the internal colonies of the urban North.

The class wanted the central oracle of the play to be an observant Muslim. Faith, when you live in the totalitarian world of the prison, is important. The conclusion of the play was the result of an intense and heated discussion about the efficacy and nature of violence and forgiveness. But by the end of a nearly hourlong discussion the class had unanimously signed off on the final scene, which I do not want to reveal here because I hope that one day it will be available to be seen or read. It was the core message the prisoners wanted most to leave with outsiders, who often view them as less than human.

The play has a visceral, raw anger and undeniable truth that only the lost and the damned can articulate. The students wrote a dedication that read: “We have been buried alive behind these walls for years, often decades. Most of the outside world has abandoned us. But a few friends and family have never forgotten that we are human beings and worthy of life. It is to them, our saints, that we dedicate this play.” And they said that if the play was ever produced, and if anyone ever bought tickets, they wanted all the money that might be earned to go to funding the educational program at the prison. This was a decision by men who make, at most, a dollar a day at prison jobs.

We read the Wilson play “Joe Turner’s Come and Gone.” The character Bynum Walker, a conjurer, tells shattered African-Americans emerging from the nightmare of slavery that they each have a song but they must seek it out. Once they find their song they will find their unity as a people, their inner freedom and their identity. The search for one’s song in Wilson’s play functions like prayer. It gives each person a purpose, strength and hope. It allows a person, even one who has been bitterly oppressed, to speak his or her truth defiantly to the world. Our song affirms us, even if we are dejected and despised, as human beings.

Prisoners are given very little time by the guards to line up in the corridor outside the classroom when the prison bell signals the end of class. If they lag behind they can get a “charge” from the guards that can restrict their already very limited privileges and freedom of movement. For this reason, my classroom emptied quickly Friday night. I was left alone in the empty space, my eyes damp, my hands trembling as I clutched their manuscript. They had all signed it for me. I made the long and lonely walk down the prison corridors, through the four metal security doors, past the security desk to the dark, frozen parking lot. I looked back, past the coils of razor wire that topped the chain-link fencing, at the shadowy bulk of the prison. I have their song. I will make it heard. I do not know what it takes to fund and mount a theater production. I intend to learn.

(First Posted on Truthdig.com on December 15, 2013)

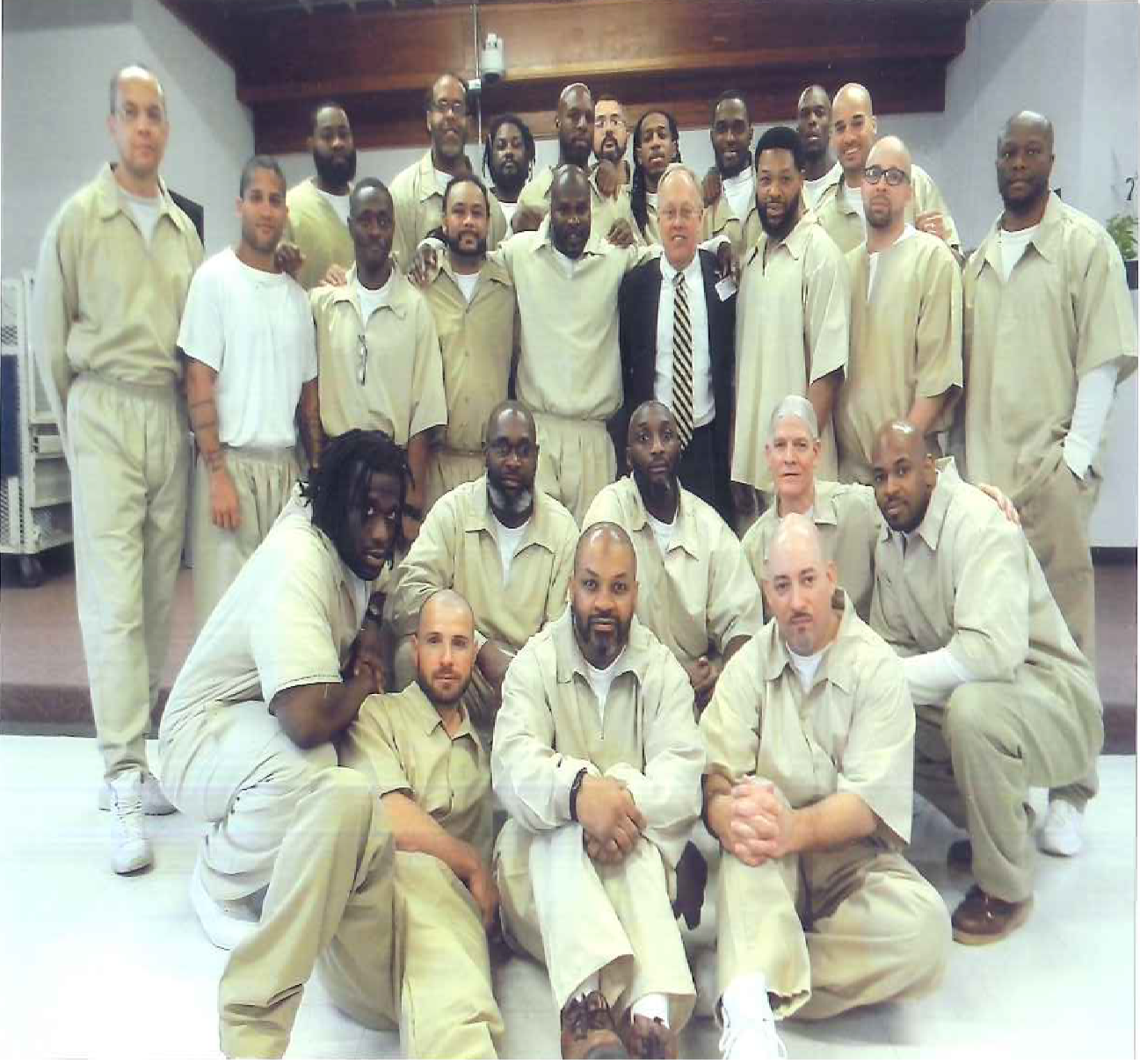

Chris Hedges is the son of a Presbyterian pastor and the part-time director of prison ministries at Second Presbyterian Church in Elizabeth, NJ. He is the former Mid-East bureau chief for The New York Times and a Pulitzer Prize winning author of several books, including War is a Force That Gives Us Meaning. His latest book is Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt. The picture that accompanies this post is of Chris with members of the class he taught in a prison in New Jersey.