Preaching in the Purple Zone: Challenges and Strategies for the Intersection of Pulpit and Public Square by Leah D. Schade

Just before the 2012 presidential election in the United States, CNN posted to its website an article by John Blake entitled, “Do you believe in a red state Jesus or a blue state Jesus”?[i] Though the question assumes a false dichotomy, the author’s observation of that election was just as applicable to the one in 2016: “Here’s a presidential election prediction you can bet on. Right after the winner is announced, somebody somewhere in America will fall on their knees and pray, ‘Thank you Jesus.’ And somebody somewhere else will moan, ‘Help us Jesus.’ But what Jesus will they be praying to: a red state Jesus or a blue state Jesus?” Blake went on to explain that both faith and elections are about choices, and that those choices are informed by how one views Jesus. The fact that many voters (and hence parishioners) often categorize themselves according to ideological lines raises the question of how preachers might approach the homiletic task of addressing controversial justice issues in such a fractured and deeply divided socio-political culture.

Of course, the divides themselves are illusions. None of us lives in a truly “red” or “blue” state. Those colors run together in our families, our houses of worship, our schools, our places of employment, and even within our own hearts and minds. Our job as preachers, then, is to find a way to courageously step into the “Purple Zone” – where the colors red and blue combine into various shades and hues. In the Purple Zone we listen with hospitality, engage with integrity and prayer, and learn with intellectual rigor in order to speak a Word that addresses the Powers, casts out demons, and proclaims the crucified and risen Christ.

The pastor’s dilemma

The challenge of addressing controversial issues from the pulpit was one I faced repeatedly as a parish pastor for sixteen years preaching in three different ministry settings – suburban (mainly white and middle-to-upper class), urban (mainly African-American working class) and rural (mainly white lower-to-middle class). While preaching justice issues was welcomed in the urban congregation I served, the two white congregations had a wide range of reactions, from affirming to pointedly negative. The dilemma is accurately described by a colleague of mine, who once confided: “On the one hand I don’t want to alienate my parishioners by saying something in a sermon that might anger them. But I also feel like I’m abdicating my pastoral and homiletical authority by not saying anything at all. At the same time, I can’t pretend that I’m in some kind of middle position on this issue, because even after looking at this from many angles, I have definite thoughts about this topic. I know I need to at least speak to it in my sermon, but I don’t know how to do it without stepping on a landmine.”

It is worth taking some time to consider why people get so contentious when talking about controversial issues. As the editors of Under the Oak Tree: The Church as Community of Conversation in a Conflicted and Pluralistic World observe:

the early twenty-first century is a season of fractiousness, especially in politics and in matters of social and economic policy, in which people often segregate into groups that engage one another not through respectful listening to others but through polemic, sound bite, caricature, manipulation, and even misrepresentation. Churches sometimes intensify such polarization with rhetorics of superiority, exclusivism, and separation.[ii]

Indeed, with any “political” issue there is much at stake: incredible amounts of wealth, questions of power and equality, personal and community identity, the ecological conditions that support life itself, and the very real persons (human and Earth-kin) affected by these issues all have a stake in our conversations, decisions, policies, and actions. Preaching in a fraught time is, of course, nothing new. Every generation finds itself in a unique confluence of cultural, political, societal and economic forces that call for preachers to draw on all of their skills, training, and gifts of the Holy Spirit in order to create sermons that are relevant, timely and effective. This moment in our nation’s, and indeed our planet’s history, however, is particularly overwrought. Because of the intense and complex overlaying of competing interests, we find ourselves, in Jesus’ words, “a house divided against itself” (Matthew 12:25). And, indeed, the oikos – meaning “house” in Greek – of our society and even earth itself is crumbling, flooding, and burning all around us. Some of us may have enough temporary wealth, power and privilege to shore up ourselves in little enclaves longer than our poorer sisters and brothers. But the frantic grasps to protect this illusory wealth only hasten the speed at which the ensuing economic and ecological domino effect will collapse the collective house of this planet.

Thus, it behooves preachers to summon their courage to address the vital issues of our time by attending faithfully to God’s Word, giving due diligence to studying the topic at hand, listening intently to their parishioners, attuning to the guidance of the Holy Spirit and “speaking truth in love” in ways that “enable congregations to genuinely hear and respond to that Word.”[iii]

The challenges of prophetic preaching

In the first two months of 2017, I conducted a survey of mainline Protestant clergy in the United States to assess how preachers are approaching their sermons during this divisive time in our nation’s history. I designed a 60-question online survey entitled “Preaching about Controversial Issues” which ran for six weeks, from mid-January to the end of February, and I received responses from 1205 participants in 45 states (with an almost equal number of male and female respondents).[iv] The survey explored a range of topics, including the following:

· The difference the 2016 presidential election has made in preachers’ willingness to address controversial justice issues in the pulpit;

· Topics clergy intended to address in the 6 months following the presidential inauguration as compared to the topics they engaged prior to the election;

· Reasons clergy list for either engaging controversial topics in their sermons, or avoiding them;

· What kind of training and support pastors are seeking to foster healthy dialogue about public issues in their congregations.

The results from this comprehensive empirical research point to current trends and emerging issues in preaching (see https://thepurplezone.net/). In addition, the information from the survey may yield insights for both clergy and congregations regarding the intersection of religion, culture, and politics, faith and public life, and the complex dynamics that gender and sexuality, race, economics, geographic locations, and political leanings of clergy and parishioners alike bring to the task of preaching.[v]

The results from this comprehensive empirical research point to current trends and emerging issues in preaching (see https://thepurplezone.net/). In addition, the information from the survey may yield insights for both clergy and congregations regarding the intersection of religion, culture, and politics, faith and public life, and the complex dynamics that gender and sexuality, race, economics, geographic locations, and political leanings of clergy and parishioners alike bring to the task of preaching.[v]

My project is building on the concept of conversational preaching to be used alongside a process known as “deliberative dialogue.”[vi] Deliberative dialogue is a process developed by researcher Scott London and used by organizations such as the National Issues Forum, which involves face-to-face interactions of small groups of diverse individuals exchanging and weighing ideas and opinions about a particular issue.[vii] I make the case that the use of conversational preaching, together with deliberative dialogue within a congregation, is an effective and potentially powerful venue for entering the Purple Zone and emerging with new insights and healthier relationships not only within the church, but for civic and public discourse in our communities and our country.

From monologue to deliberative dialogue

Some respondents to my survey noted concern about sermons being a one-way monologue which precludes the opportunity for people to ask questions and engage in dialogue. It is this misconception – that preaching is only a monologue – that I dispute. I contend that it is not only possible but necessary, fundamental, and life-giving to the task of preaching that pastors address controversial topics not as fodder for soap-box diatribes, but as opportunities to deepen and build upon the relationships within the congregation and community. The process of deliberative dialogue in conjunction with accompanying sermons is one way that the conversation model can be implemented. I suggest this model as an option for effectively addressing controversial topics and opening a way for the Holy Spirit to work within a politically diverse congregation. The preaching-deliberative-dialogue process may even offer a way for healing to take place in communities where damage has been sustained and pain has been endured over contentious issues – because for some, entering the Purple Zone can also connote the bruising one endures when stepping into that place of controversy and divisiveness.

However, in the courses I’ve taught and workshops I’ve led, I’ve found that with training and skill-building, along with establishing scriptural and theological principles for engaging controversial issues in their sermons, preachers are better equipped with strategies for “preaching in the purple zone.” We are beginning to see how discipleship and citizenship intersect and what potential there is for the church’s civic role in strengthening American democracy.

Conclusion

Preaching in the Purple Zone is primarily about answering God’s call to be a prophetic witness in the face of injustice. And while there are obvious hazards in attending to this call, it need not necessarily lead to further rupturing of relationships. Based on my experiences as a pastor engaged in various kinds of advocacy and activism, as well as my research thus far, some keys to faithful prophetic preaching are: 1) establishing trust and respect with those in our churches; 2) encouraging the sharing of personal stories to humanize the difficult issues with which we are grappling; 3) listening deeply and reflectively; 4) moving beyond negative generalizations and stereotypes about the side with which we disagree; and 5) finding common values shared amongst people in the dialogue group upon which to build or deepen relationships, and perhaps take action on a particular issue. Overall, the preaching-dialogue process aims to help transform the culture of a congregation from one of divisiveness to a culture of conversation.

Most importantly, faith in the guiding of the Holy Spirit, the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, and the love and forgiveness of God are powerful resources within the church that can be activated through prayer, worship, Bible study, service, and fellowship. We enter the Purple Zone sustained by this divine love, knowing that “there is no fear in love. But perfect love drives out fear” (1 John 4:18a). Drawing from this love in the midst of our preaching and pastoring invites us to “speak truth from a deep place of passion and compassion.”[viii] My hope is that the insights gained from this work will be helpful for clergy to enhance their skills in preaching, dialogue facilitation, and church leadership.

[i] Blake, John, “Do you believe in a red state Jesus or a blue state Jesus?” CNN, Nov. 2, 2012, http://www.cnn.com/2012/11/02/politics/red-blue-state-jesus/

[ii] Ronald J. Allen, John S. McClure and O. Wesley Allen, editors, Under the Oak Tree: The Church as Community of Conversation in a Conflicted and Pluralistic World, (Eugene, OR, Cascade Books, 2013), xvi.

[iii] Leonora Tubbs Tisdale, Prophetic Preaching: A Pastoral Approach, (Louisville, KY, Westminster John Knox, 2004), xiii.

[iv] I calculated my optimal sample size (1051) based on information collected from the statistics and research departments of eight mainline Protestant denominations to arrive at an estimate of the total number of pastors currently serving congregations. While I received responses that represented over 16 different denominations, I calculated my sample pool (67,701) based on the number of active, non-retired clergy currently serving congregations in eight denominations in the United States – United Methodist, Presbyterian Church – USA, Episcopal, Lutheran (ELCA), American Baptist, United Church of Christ, Disciples of Christ (Christian Church), and Reformed Church in America. The number of responses (1205) exceeded the optimal sample size needed for a statistically accurate sampling at a confidence level of 95% with a 3% margin of error. It is important to note that not all questions were completed by all participants, so the confidence level and margin of error is adjusted accordingly for each question.

[v] Survey questions included all of these demographic subgroups, as well as education level, bi-lingual and immigration status, age, and ministerial status.

[vi] The concept of conversational preaching was developed by Lucy Atkinson Rose in Sharing the Word: Preaching in the Roundtable Church (Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox, 1997). The book Under the Oak Tree: The Church as Community of Conversation in a Conflicted and Pluralistic World (Eugene, Or: Cascade Books, 2013), edited by Ronald J. Allen, John S. McClure and O. Wesley Allen, also used the concept of conversational preaching as a premise for its collection of essays.

[vii] http://www.scottlondon.com/reports/dialogue.html

[viii] Tisdale, 106.

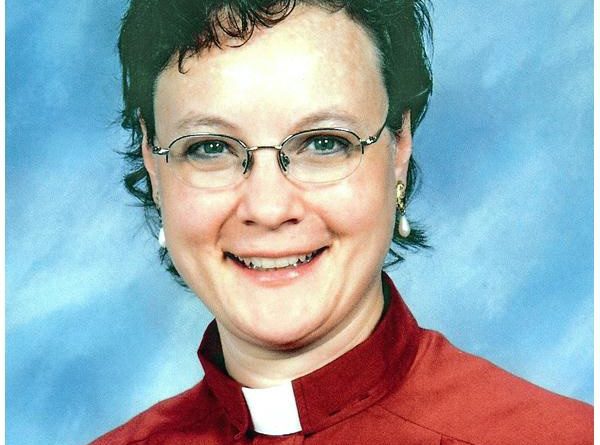

The Rev. Dr. Leah D. Schade is the Assistant Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary in Lexington, Kentucky. An ordained pastor in the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America for 17 years, Leah has served congregations in rural, urban, and suburban settings. She earned both her MDiv and PhD degrees from the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Philadelphia, and completed her dissertation focusing on homiletics and ecological theology. Her book Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015) is available at www.chalicepress.com. She is also the “EcoPreacher” blogger for Patheos.com: http://www.patheos.com/blogs/ecopreacher/.