Palestinian Liberation Theology as Resistance – by Kathleen Christison

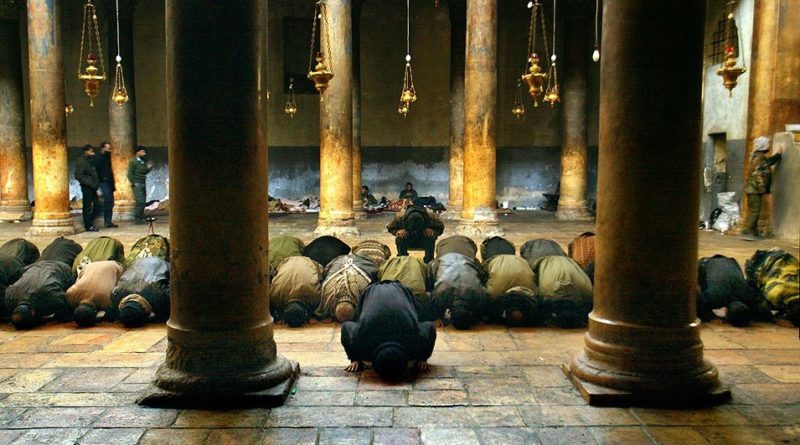

Photo above: Palestinian children celebrating Christmas in Bethlehem and wearing the Keffiyeh (scarf) which is the key symbol of Palestinian resistance.

Editorial note: This is an excerpt from the forthcoming book, Why Palestine Matters, The Struggle To End Colonialism. This article appears in Chapter 7 entitled “Resistance.” See the book’s website for more info: WhyPalestineMatters.org. The book is published by theIPMN.org, The Israel Palestine Mission Network of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.).

Although often thought to enjoy special favor from Israel, Christian Palestinians in Israel and the occupied territories live under the same Israeli oppression as Muslims. They were subjected to ethnic cleansing along with Muslims during the 1948 Nakba and face the same limitations today on their liberties. They are as inclined toward resistance to Israeli domination as are Muslims.

And although constituting only a tiny minority among Palestinians because of large-scale emigration during the twentieth century, there remain tens of thousands of Christians in historic Palestine. Palestine and Jerusalem are the very heart of all Christianity. Not only are the regional heads of several Christian denominations seated in Jerusalem, but Palestinian Christians trace their origins to Jesus’ time. For those still there, the determination to stay, their sumud, arises from the belief that they are descended from the earliest Christians and that their struggle for justice is divinely ordained.

As in Latin America, where liberation theology developed in the 1950s and ’60s as a theological balm and empowerment for the poor and oppressed, Palestinian liberation theology focuses on liberating Palestinians from the oppression of Israeli domination through Jesus Christ’s example in the gospels. As a modern contextual theology that developed from a range of social and historical contexts, liberation theology is adaptable to any situation in which faith practitioners suffer injustice. Black theology was developed by noted theologian James Cone in several books written over four decades, including the early Black Theology and Black Power and his recent The Cross and the Lynching Tree. In today’s intersectional world, other oppressed populations and groups—for instance, Feminist and Womanist groups, and Latinx[1] populations in the US—have also developed their own liberation theologies.

In its own context, Palestinian liberation theology has been concerned with the central claim of religious Zionists that, in the Old Testament, God made a holy covenant with the Jewish people in which the land Palestinians lived on for centuries was given to the Jews for their exclusive use. Seen through the Palestinian Christian lens, this God is unjust. Their liberation theology concludes that there simply can be no such God because there is one true God who bestows justice on all.

The principal beliefs of Palestinian liberation theology were formulated under the guidance of Palestinian Episcopal priest Naim Ateek and propounded through the organization Sabeel—the Sabeel Ecumenical Liberation Theology Center in Jerusalem. The Arabic word sabeel, meaning “the way,” was adopted because the first Christians called themselves “people of the Way.”

Although his writings are primarily for Christians, Ateek envisions liberation for all Palestinians in everyone’s particular context. His own context is Christ-centered, but he feels he has a responsibility to others and works for liberation not only for Palestinian Christians and Muslims, but even for Israelis. He is leading Christians to resist any biblical interpretation, whether by Jewish or by Christian Zionists, that diminishes Palestinian equality by claiming Jewish chosenness and Jewish supremacy in the land.

In his early enunciation of Palestinian liberation theology almost thirty years ago in Justice and Only Justice, Ateek voiced questions about God on behalf of Palestinian Christians, noting that the injustice under which they live causes them to question the very character of God. “Is God partial only to the Jews? Is this a God of justice and peace?” he wondered. “The focus of these questions is the very person of God. God’s character is at stake. God’s integrity has been questioned.”

This theology is a resistance that derives from the core of the Christian message as well as the Israeli colonization of Palestine; it therefore speaks to all Palestinians, Muslim as well as Christian. By definition, Palestinian liberation theology challenges Zionist founding principles of exclusive Jewish rights to the land. It is also a resistance to both Christian Zionism and mainstream post-Holocaust Protestant theology, both of which turn a blind eye to Israeli oppression of Palestinians, but for different reasons. Both may be characterized as “orientalist” in their bias against Palestinians and other Arabs. Christian Zionism supports Israel uncritically as a part of its doctrine of the “end days” and the second coming of Jesus, while mainstream post-Holocaust Protestant theology overlooks Israeli violations of international law and human rights as a form of repentance for centuries of Christian antisemitism.[2]

Church leaders in Palestine have protested the virtually forgotten plight of Christians under Israeli rule, but in 2009, there was an unprecedented gathering of all the heads of churches in Jerusalem and Palestine which resulted in the confessional document they called Kairos Palestine. It takes its cue from the 1985 South African Kairos document and is a plea for solidarity and action from Christians around the world for the plight of Palestine. It has been deemed controversial because it calls for nonviolent protest through economic actions such as boycotts, but Kairos Palestine stands as a declaration of resistance to Israeli oppression and a challenge to Western Christian churches to cease their acquiescence in that oppression.

Kathleen Christison has been writing on the Palestinian situation for 45 years, first as a CIA political analyst in the 1970s and since then as a freelance writer. She has traveled to Palestine more than a dozen times, initially in 1963 and with increasing frequency since 2003. She writes often for Counterpunch.org, and is a member of EPF/PIN, the Episcopal Peace Fellowship’s Palestine-Israel Network. Her books include Perceptions of Palestine (1999 and 2001), The Wound of Dispossession (2002), and Palestine in Pieces (2009), co-authored with her late husband Bill Christison. She is currently working on a Master of Theological Studies degree, focusing on Liberation Theology, at the Iliff School of Theology in Denver.

Kathleen Christison has been writing on the Palestinian situation for 45 years, first as a CIA political analyst in the 1970s and since then as a freelance writer. She has traveled to Palestine more than a dozen times, initially in 1963 and with increasing frequency since 2003. She writes often for Counterpunch.org, and is a member of EPF/PIN, the Episcopal Peace Fellowship’s Palestine-Israel Network. Her books include Perceptions of Palestine (1999 and 2001), The Wound of Dispossession (2002), and Palestine in Pieces (2009), co-authored with her late husband Bill Christison. She is currently working on a Master of Theological Studies degree, focusing on Liberation Theology, at the Iliff School of Theology in Denver.

[1] Latinx (pronounced lateenex) is a gender-neutral term often used in place of Latino or Latina to designate persons who trace their ancestry to Latin America and/or have social and cultural ties with Latin America.

[2] The book that this article is excerpted from uses the spelling “antisemitism.” Jewish Voice for Peace explains in their book published on the topic that the use of the hyphen and upper case, as in “anti-Semitism,” legitimizes the pseudo-scientific category of Semitism, which sorts humans into different races, justifies racial hierarchies, and argues for discrimination, supremacist policies, and worse. See “A Note about the Spelling of ‘Antisemitism’” in On Antisemitism: Solidarity and the Struggle for Justice, page xv, Haymarket Books, 2017.