The Boondoggle over Critical Race Theory by Rubén Rosario Rodríguez

The dictionary defines “boondoggle” as “work or activity that is wasteful or pointless but gives the appearance of having value.” The recent uproar over the teaching of Critical Race Theory (CRT) in public schools is the very embodiment of a boondoggle: (1) there is no evidence that CRT is part of the K-12 curriculum anywhere in the country; (2) nevertheless, 28 states have introduced legislation banning or restricting the teaching of critical race theory in public schools grades K-12; and (3) another 15 states have introduced legislature adding critical race theory to the K-12 curriculum. This is political demagoguery at its worst and can be seen as part of President Trump’s political legacy that not only refuses to die, but seems to be setting the national agenda for the GOP despite his electoral loss in 2020. In the past four months, Fox News has mentioned critical race theory over 1,300 times in their news coverage, turning CRT into “a new boogie man for people unwilling to acknowledge our country’s racist history and how it impacts the present.” In other words, CRT has become a conservative talking point as part of an intentional strategy to confuse the issues and undermine efforts to confront racial injustice in this country.

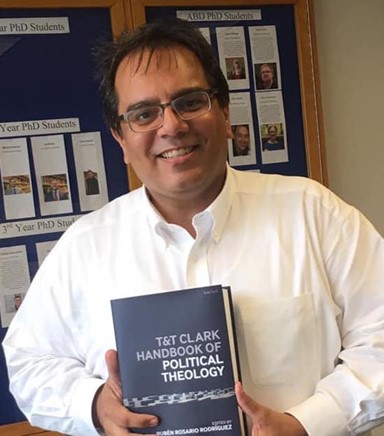

In 2008 I published a book called Racism and God-Talk: A Latino/a Perspective that introduced readers to—and meaningfully engaged—critical race theory. My book sales sure would have benefitted from today’s controversy, but back in 2008—despite the fact that one of the Presidential frontrunners was the man who eventually became the nation’s first African American President, Barack Obama—nobody was concerned or frightened by critical race theory. Though there was a previous controversy in 1993 when President Bill Clinton nominated law professor Lani Guinier to head the Justice Department’s civil rights division but she withdrew her nomination after political opponents made public some of her earlier legal writings that employed critical race theory, it is only in recent history that CRT has become a matter of national conversation. What is Critical Race Theory? Why is it controversial?

Critical race theory began within critical legal studies and its central premise is easily understood: “any analysis of American society must take into account its history of racism and the role race has played in shaping attitudes and institutions.” CRT’s most obvious application has been within civil rights law in efforts to eliminate segregation, racially motivated redlining (the denial of services to residents of specific neighborhoods or communities), and most  recently—in reaction to the killing of George Floyd in 2020—to draw attention to the long and troubled history of police brutality against black citizens. CRT is closely tied to the concept of white supremacy, which contends that US society is structured to maintain and defend white power and privilege, and focuses on systemic racism, or the way “procedures and institutions work to perpetuate racial inequity even in the absence of personal racial animus.”

recently—in reaction to the killing of George Floyd in 2020—to draw attention to the long and troubled history of police brutality against black citizens. CRT is closely tied to the concept of white supremacy, which contends that US society is structured to maintain and defend white power and privilege, and focuses on systemic racism, or the way “procedures and institutions work to perpetuate racial inequity even in the absence of personal racial animus.”

Sadly, rather than focus on the harm caused by hundreds of years of white power and privilege, the national conversation remains focused on critical race theory. Actually, let me correct that. The national conversation has ignored critical race theory and has instead focused on what conservative activists and news pundits want us to believe. Critical Race Theory is: (1) Marxist propaganda, (2) trying to make white people feel guilty about being white, (3) a cult trying to brainwash our children, and (4) an attempt to erase our proud national history. No scholar has employed critical race theory to blame white people today for the actions of white people in the past; however, critical race theory does say that “white people living now have a moral responsibility to do something about how racism still impacts all of our lives today.” It is time that we as Christians stop allowing Fox News and other conservative media outlets to set the terms of our national conversation. More to the point, it is time that we stop them from defining what is or is not Christian. There is room within the good news of Jesus Christ for critical race theory.

The real fight over critical race theory and white supremacy is over political power. Who has it, who wields it, and to what end. Trump’s appeal to the Alt-Right and white nationalism simply brought out into the open the racist and white supremacist core festering in the heart of our culture. As a liberation theologian, I view the church as a counterculture resisting oppression and defending human dignity, even while recognizing that the institutional church has often served the oppressors instead of the oppressed. Unfortunately, as Christians we are fighting a myth whose hold on the American imagination is greater than the church’s preaching—the myth of American  exceptionalism that fueled westward expansion and gave rise to the ideology of Manifest Destiny. This same ideology has given rise to a white Christian political theology whose motto is Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign slogan––Make America Great Again—with the implied understanding that we are returning to the pre-Civil Rights era when things were great for white people only. If we are going to rescue the church and the gospel of Jesus Christ from the hands of white Christian extremists, then we need to reject the boondoggle over critical race theory and shine the national spotlight where it belongs: the continuing suffering of black and brown lives at the hands of a society and a political system designed to maintain white power and privilege. As pastors, theologians, and church members we cannot accept a neutral stance nor tolerate further oppression in the name of political stability. To paraphrase Dr. King’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail: it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of oppression to say, “Wait.”

exceptionalism that fueled westward expansion and gave rise to the ideology of Manifest Destiny. This same ideology has given rise to a white Christian political theology whose motto is Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign slogan––Make America Great Again—with the implied understanding that we are returning to the pre-Civil Rights era when things were great for white people only. If we are going to rescue the church and the gospel of Jesus Christ from the hands of white Christian extremists, then we need to reject the boondoggle over critical race theory and shine the national spotlight where it belongs: the continuing suffering of black and brown lives at the hands of a society and a political system designed to maintain white power and privilege. As pastors, theologians, and church members we cannot accept a neutral stance nor tolerate further oppression in the name of political stability. To paraphrase Dr. King’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail: it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of oppression to say, “Wait.”

We all live with regret. One regret I will take to my grave is that when I wrote Racism and God-Talk in 2008 I made a conscious decision to avoid discussing white supremacy. In the book I talked about white power and privilege, but I never labeled it white supremacy, and consequently—despite my engagement and use of critical race theory—I undermined my own efforts to resist racism and strive for racial justice. Why did I do it? In part because after serving a mainline, white congregation in the Midwest for five years prior to researching and writing this book, I was convinced that the only way to engage middle class, white, mainline congregations in the US was through persuasion. Rather than confront them with the ugly realities of racism, and risk alienating my audience, I sugarcoated the facts and tried to make them more palatable. Today, if I could go back in time, I would do it differently. I wouldn’t dull the prophetic edge from my words but would have named the evil of white supremacy clearly and distinctly for my readers. Would it have helped book sales? They can’t get much lower. Would it have made a difference? Probably not, but I would sleep better at nights knowing I didn’t contribute to the complacency that continued to tolerate police brutality against black and brown lives.

If there is any comfort to be found in all this mess it is that few scholars saw the return of an overt white nationalism and white supremacy like we have witnessed since the 2016 Presidential election. One prophetic voice that saw it coming and did not stay silent was my former professor James H. Cone, who accurately diagnosed the persistence of white supremacist culture in the US since the Civil War in his powerful book, The Cross and the Lynching Tree (2011): “Although the southerners lost the Civil War, they did not lose the cultural war–the struggle to define America as a white nation and blacks as a subordinate race unfit for governing and therefore incapable of political and social equality” (6). It is time we Christians reject the god of white supremacy and discover the God of black theology—the God of the Bible—who became incarnate in the midst of poverty, became a political exile, lived among the outcast of society, and died broken and mutilated at the hands of law enforcement.

N.B. The first image is the cover of my first book; the second is entitled “Warren Street School Entrance Sign,” and is shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. You are free to share, copy, and transmit the work so long as you give proper attribution. The photographer is identified as: ChoiChoi4life.

The Rev. Dr. Rubén Rosario Rodríguez, a graduate of both Union Theological Seminary in New York and Princeton Theological Seminary, is a Professor of Systematic Theology in the Department of Theological Studies at Saint Louis University. His work bridges systematic/constructive theology, theological ethics, and political theology, and he is currently working on a monograph entitled Theological Fragments for a Fractured World (forthcoming from Westminster John Knox Press). He is the author of Racism and God Talk: A Latino/a Perspective (New York University Press, 2008), Christian Martyrdom and Political Violence: A Comparative Theology with Judaism and Islam (Cambridge University Press, 2017), Dogmatics After Babel: Beyond the Theologies of Word and Culture, and editor of the T&T Clark Handbook of Political Theology (Bloomsbury/T&T Clark, 2019).

The Rev. Dr. Rubén Rosario Rodríguez, a graduate of both Union Theological Seminary in New York and Princeton Theological Seminary, is a Professor of Systematic Theology in the Department of Theological Studies at Saint Louis University. His work bridges systematic/constructive theology, theological ethics, and political theology, and he is currently working on a monograph entitled Theological Fragments for a Fractured World (forthcoming from Westminster John Knox Press). He is the author of Racism and God Talk: A Latino/a Perspective (New York University Press, 2008), Christian Martyrdom and Political Violence: A Comparative Theology with Judaism and Islam (Cambridge University Press, 2017), Dogmatics After Babel: Beyond the Theologies of Word and Culture, and editor of the T&T Clark Handbook of Political Theology (Bloomsbury/T&T Clark, 2019).